Brand Archetypes: Popular, Prevalent, and Fundamentally Flawed

Published on

Reading Time

4 mins

Brand archetypes have become a popular tool for consultants and marketers in recent years, but are they as effective and useful as people like to believe? Or are they simply a bunch of twaddle, as some industry experts have hinted? Here is my take on the rise of brand archetypes and why I think businesses should approach them with real caution.

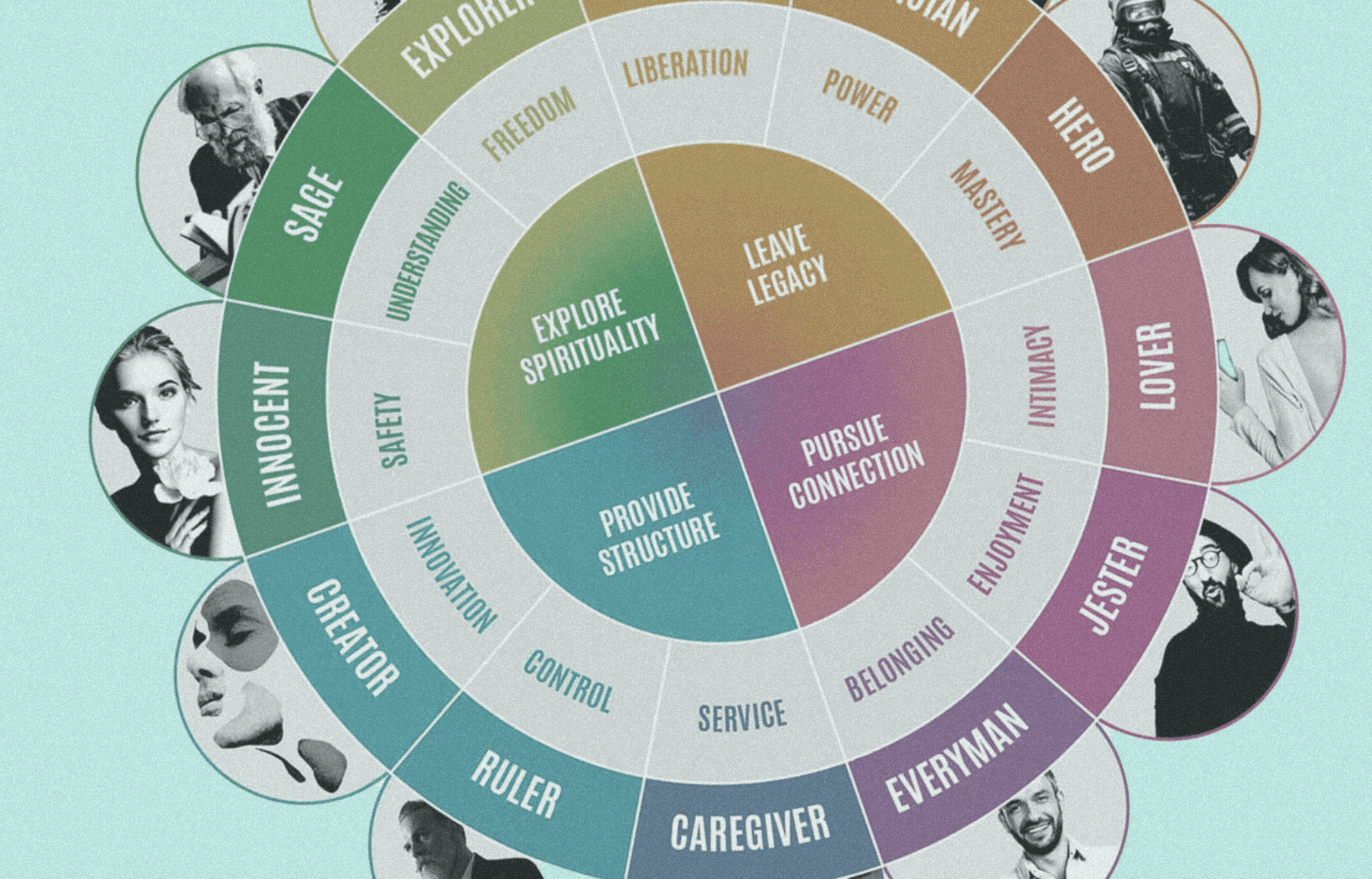

Brand archetypes originated from the work of Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung. Jung introduced the idea of archetypes in 1919 as universal patterns embedded in the human psyche. While his ideas centred on psychology and mythology, the marketing world adopted them much later. Consultants began using archetypes as a framework to create brand personalities and supposedly strengthen brand identity.

I once shared a post on LinkedIn from marketing professor Mark Ritson. He described brand archetypes as "total bollocks but incredibly prevalent," placing them second on his table of The All-Time Marketing BS Index. My own comment was not much softer, calling them "esoteric nonsense that only fulfils the ego of the facilitator."

Unsurprisingly, some so-called experts were quick to message me defending brand archetypes as a "valuable tool." Valuable to whom, I wondered.

Why people use brand archetypes

Before pulling them apart, it is worth understanding why archetypes are still so popular in branding. For many, archetypes offer a shortcut. They simplify the challenging task of defining a brand’s personality. They provide a ready-made framework that helps teams rally around an idea. In that sense, they can be useful for workshops, alignment, and making abstract thinking feel more tangible.

Archetypes also carry a certain intellectual sheen. Rooted in Jungian psychology, they make branding feel weightier and more academic. They look great in a pitch deck. They impress stakeholders. They add a sense of depth where there is often none.

And in internal meetings, archetypes help non-creatives engage. It is easier to say “We are the Explorer” than to define a grounded personality from scratch.

But ease and engagement are not indicators of effectiveness. Which leads to the real issue.

Why brand archetypes are fundamentally flawed

I have seen brand archetypes from both sides. I have facilitated archetype workshops, and I have been the client sat in one. There is no denying that archetypes are engaging. Teams understand them quickly and enjoy choosing their category. It feels like movement.

Until it doesn’t.

Because once the excitement fades, reality shows up. Now teams have to explain to the wider business that the brand is apparently the “Sage” or the “Explorer.” Try doing that across multiple regions or departments, especially in non-English speaking environments.

I remember one workshop where someone asked, “Wouldn’t it be clearer to just share our brand traits and values rather than align to an archetype that no one outside this room will understand?” It was a perfectly reasonable point. And I remember fumbling to offer a convincing answer.

Limiting, ambiguous and often just nonsense

Here is the core problem. Brand archetypes claim to offer clarity, but more often they create confusion. They are vague enough to be interpreted differently by different people, yet rigid enough to box a brand into a narrow set of behaviours. They create the illusion of differentiation, but in reality they encourage sameness.

Look at healthcare branding. Most companies fall into the Caregiver or Sage archetype. CVS Health? Caregiver. Johnson & Johnson? Caregiver. Mayo Clinic? Sage. Not exactly distinctive.

Supporters argue that archetype ambiguity allows room for interpretation. In truth, it creates inconsistency. And in branding, inconsistency is a silent killer.

And consider Harley-Davidson, the classic Rebel. But does every piece of communication need to scream rebellion? Are brands no longer allowed nuance? Humans certainly are.

Archetypes often lean into what the company wants to be, rather than what the customer needs it to be. That misalignment creates brand expression that feels contrived, forced or simply out of touch. To quote Marty Neumeier: “A brand is not what you say it is. It’s what they say it is.”

When archetypes derail customer understanding

A growing trend is not just using archetypes for brand personality, but for customer personality too. This creates even more confusion.

Imagine a mid-size travel company. The team decides they are the Explorer archetype. Fair enough. They sell experiences and adventure. Then someone suggests, “Our customers are Explorers too. That is why they book with us.”

Suddenly, marketing starts speaking to rugged solo travellers, promoting remote escapes and wild challenges. But the actual customer base? Middle-aged professionals booking curated tours in Tuscany. They want reassurance, comfort, and expertise, not adventure metaphors.

This is what happens when you replace genuine customer insight with character labels. You end up marketing to an imagined personality, not the real person making the booking. And that damages trust and relevance.

What to do instead of relying on brand archetypes

Look outward. Your customers should shape your brand expression, not a mythological character.

Understand their beliefs, behaviour, frustrations and aspirations. Customer insight and sociographic profiling consistently outperform archetype thinking because they are rooted in reality, not metaphor. This leads to tone, personality and messaging that actually resonates.

Then look at your competitive landscape. Understand where others play. Identify spaces they ignore. Real differentiation lives in the gaps, not in a pre-assigned archetype.

The false science behind archetypes

Proponents often lean heavily on psychology to justify archetype usage. Jung. Freud. The subconscious. It sounds credible. But this is where the logic collapses.

Yes, Jung created the idea of archetypes. But he did not create the 12 brand archetypes used in marketing. Those were invented in the book "The Hero and the Outlaw" in 2001. Meanwhile, modern psychology has moved far beyond Freud and Jung. We are not dealing with validated psychology. We are dealing with marketing dressed up as science.

Claiming scientific legitimacy because you reference Jungian theory is like claiming a diet is medically proven because it mentions vitamins.

The consistency paradox

Archetypes are marketed as tools for consistency. In practice, they often create the opposite. Teams argue endlessly about whether a campaign is “Hero enough” or whether the typography fits the “Innocent” personality. The archetype becomes a creative straightjacket that slows decision-making.

Meanwhile, different teams inevitably interpret the archetype differently. Your London office’s interpretation of Explorer looks nothing like your New York office’s version. Consistency disappears.

Not just my opinion

I am not alone in this. Aside from Mark Ritson, other respected voices have criticised archetypes for being overly simplistic and lacking empirical grounding. Byron Sharp has dismissed them as ignoring the real drivers of consumer behaviour. Tom Goodwin has compared them to astrology. Helen Edwards has argued that brands are inherently multidimensional and forcing them into fixed archetypes diminishes their richness.

Even Carl Jung himself warned against misusing archetypes. In "The Archetypes and The Collective Unconscious" he wrote:

"Those who do not realise the special feeling tone of the archetype end with nothing more than a jumble of mythological concepts, which can be strung together to show that everything means anything or nothing at all."

Exactly.

Final thought

I understand the appeal of brand archetypes. They make workshops easier. They create a sense of progress. They offer fast answers. But when it comes to shaping a brand that resonates with real people and stands out in competitive markets, archetypes fall short.

Businesses deserve better than shortcuts dressed as strategy.

And perhaps this is just me. I am a bit of an Outlaw after all.